J. Casale - W2NI

The Vail Register

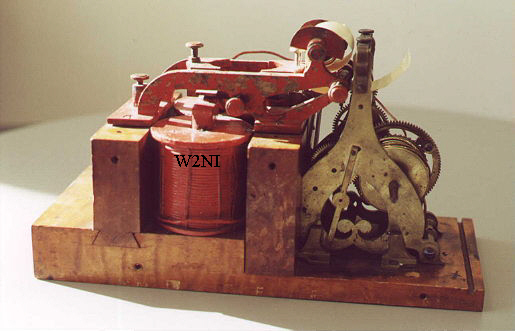

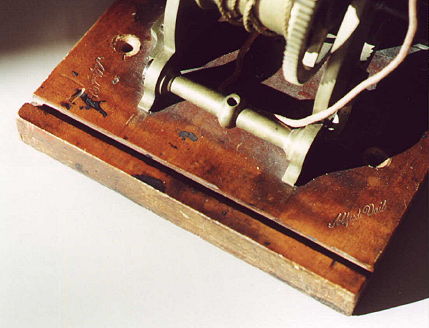

The Vail Register as it appears today at Cornell University |

In preparation for the article about Samuel Morse's farewell message, I started to accumulate material about the Vail register and felt its historical significance demanded its own article. The register, as with the labors of its designer, have received minimal recognition over the years. I recently had the unique opportunity to spend two days examining this National treasure at Cornell University. In this article, I will attempt to describe and document what I found there.

On March 3, 1843 a bill granting 30,000 dollars for an experimental telegraph line was passed by the U.S. Senate and signed that same day by President Tyler. Samuel Morse named Alfred Vail as one of his three assistants, giving him the responsibility to superintend the machinery requirements for the new line between Washington and Baltimore. Vail, in his March 21st acceptance letter to Morse states his responsibilities in part :"As an assistant...I can superintend and procure the making of the instruments complete according to your direction, namely; the registers, the correspondents with their magnets, the batteries, the reels, and the paper..." Work began on the instruments shortly thereafter. Vail's design for two registers was finalized in early 1844 and his drawings were given to Mr. John Stokell, a New York City clock maker, for final assembly. On April 1, 1844 the construction of the aerial line began in Washington under the supervision of Ezra Cornell. One of the two registers built, was placed at the Capitol under Morse's control. The second register was transported from place to place by Vail, in order to test each new segment of the line with Morse, as they progressed north towards Baltimore.

After Vail received that historic message in Baltimore, he kept the register in a hallway case at his home. Alfred Vail passed away in January of 1859 and, in his will, bequeathed all his telegraph instruments to Samuel Morse with the exception of his Baltimore register, which he willed to his eldest son Stephen. Stephen Vail had the register until 1873 when it was loaned for two consecutive exhibitions, first at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City until 1876/77, then, at the National Museum in Washington until 1898. During 1897, Vail decided to sell his father's register and offered it to Mr. J. Schurman, the president of Cornell University at a "reduced" price of 1000 dollars. Schurman, who; " knew of no one willing to give 1000 dollars for this purpose" gave Vail's letter to Professor R.H. Thurston, who suggested to Vail that he write each of the seven trustees of the University. A positive response was returned from representatives of the estate of Hiram Sibley, who provided the funds for its purchase. Sibley, as with the University's founder, Ezra Cornell, have deep roots in the history of the telegraph in America. In March of 1898, Vail directed the Smithsonian to box the register and ship it to Cornell University, where it has been ever since. The Smithsonian was obviously disappointed with its departure, but, according to Vail ; "..they have expressed great desire to purchase it, but funds were too low".

|

|

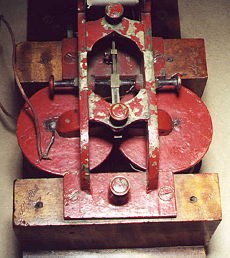

The three pens pointing upwards to the roller. |

All later embossing registers used Vail's

|

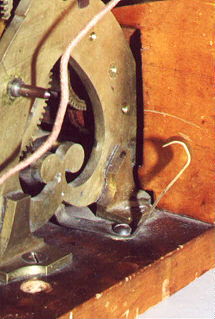

The original pen lever return spring is missing. Vail originally used a long steel wire spring that went from a binding post, on the top end of the register, to a yoke on the bottom of the lever near the pens. This wire ran almost parallel with the lever. In its place is a much newer coil spring going between the bottom of the pens to a new arm near the clockwork. The original spring still appeared in photographs taken in 1895. A replacement spring could easily be made, though, and all the original hardware is still there.

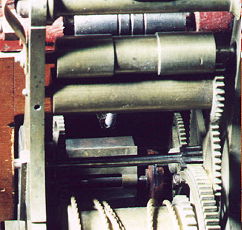

A close-up view of the governor.

|

The "break" consists of a simple brass

|

Located near the bottom of the clockwork and nestled into the wood by one inch, is a simple, fixed-pitch, two vane governor that was used to help maintain a constant speed by spinning against the resistance of the air. The governor shows a very early modification. On top of the leading edge of each vane is a copper strip that was attached by poured solder. This modification increased the overall surface area of the vanes by 31 percent, providing the additional drag to slow down the clockwork.

A sample of the print from the register.

|

Cosmetically, the magnets and brass frame are painted in a bright red paint that is fading and chipping from the brass. A carpenter's scribe marks are still visible where they were used for centering, and to outline the cutting of the dovetail joint. The hardwood base appears to have been coated with shellac and the bottom was left untreated. The brass clockwork is just press fitted in place within its four anchors.

Unlike the angelic harp-like-patterned registers that were used in the 1850-60's, this register's design is a practical one. The solidly built, 157 year old register could go back to work tomorrow if required. With fresh connections to its magnets, a weight, and a reel of paper, it would perform effortlessly all day long. All of its stops are still adjusted perfectly to produce a clear print sample; almost as if it was just pulled out of service. The last significant demonstration of its abilities appears to have been in 1944, for a centennial encore of the first message.

The sound of it is quite impressive. When depressing the pen lever against its stops, it produces a deep solid sound that is fully absorbed within its base. None of its resonance makes it to the table underneath. There is only a trace of reverberation coming from the "new" spring.

You may be wondering what happened to the register at Morse's station in Washington. In a conversation Stephen Vail had with Morse, Morse told him: "that the instrument in his charge at Washington had disappeared and he knew nothing of its existence."

Two of the nine signatures by Alfred Vail. |

"This lever and roller were invented by me in the sixth story of the New York Observer office, in 1844, before we put up the telegraph line between Washington and Baltimore... I am the sole and only inventor of this mode of telegraph embossing writing. Professor Morse gave me no clue to it... and I have not asserted publicly my right as first and sole inventor, because I wished to preserve the peaceful unity of the invention, and because I could not, according to my contract with Professor Morse, have got a patent for it. "

Vail's attached note to the singular telegraph heirloom of his last will and testament, is convincing evidence that his wish was to isolate, protect, and provide for history, his register, along with a record of its significance. Vail's 1837 contract with Morse gave him one quarter interest in the invention, ( later reduced to one eighth ) but he never realized any wealth from it. Significant wealth was made, though, by stockholders of successful telegraph companies. Fortunately, due to the generosity of Ezra Cornell and Hiram Sibley, Alfred Vail's original wishes are effectively being granted.....